Demographic “Dividend” in Future Māori and Pacific Population Shifts.

Demographic “Dividend” in Future Māori and Pacific Population Shifts.

It’s partly cloudy here in Taumarunui, and a large group of Māori high school students have walked past my house on their way to school. On the golf course down the end of my street, three groups of elderly, Pākehā people are teeing off at the third hole. I’m about to head into town to buy some milk. Four of the dairies are Indian owned as is our New World supermarket. Tonight I might have Thai, Chinese or Indian kai for dinner. Such is the growing multicultural makeup of our town, that I thought of an interview I did with Bev Cassidy McKenzie, the former CEO of Diversity Works in Auckland back in 2017.

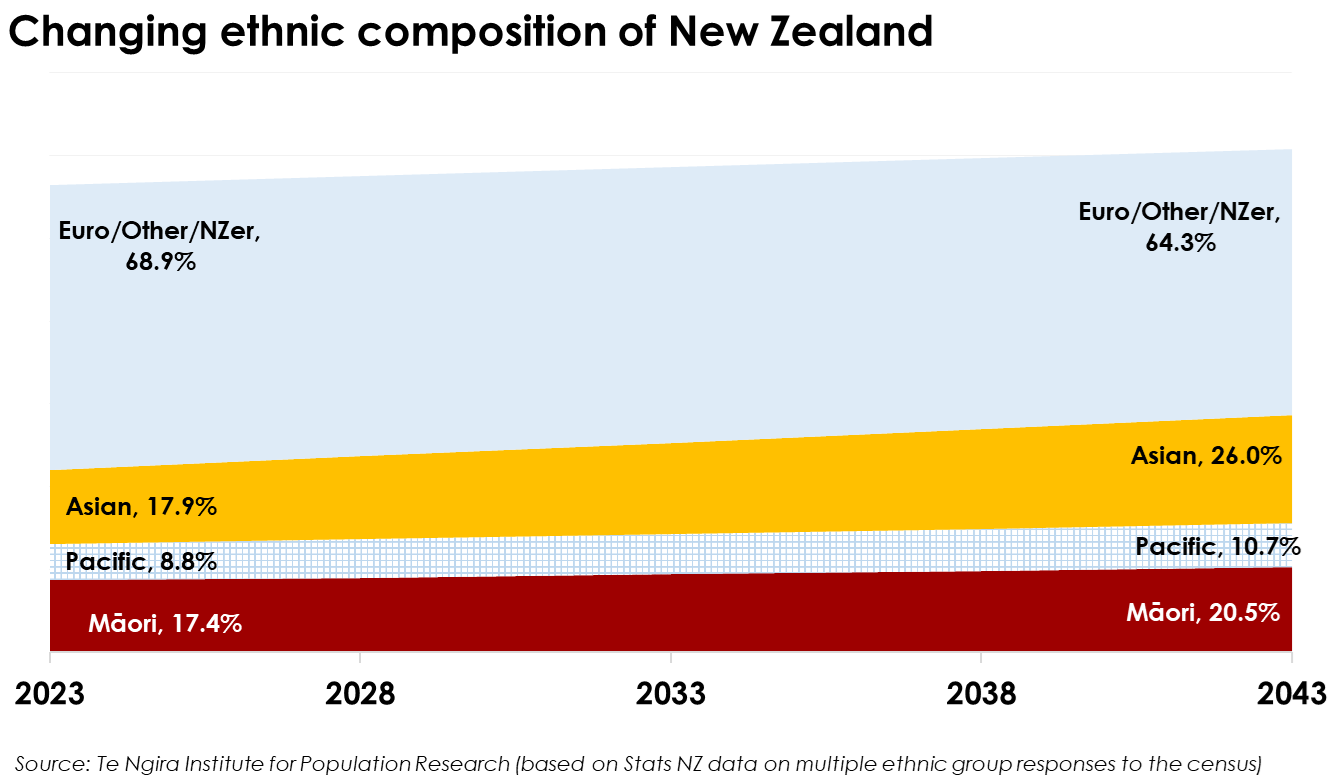

She said if NZ was a village of 100 people, 14 would be Māori, 11 would be Asian and 7 would be of Pacific descent. Those populations are set to increase faster than New Zealand’s Pākehā population over the next two decades (Statistics NZ, Census 2013). Statistics NZ predicted that by 2038, 22% of the population will be Asian, 18.4% Māori and 10.2% Pacific.

So by 2038, more than half of New Zealand’s population will be non-Pākehā. Economist Shamubeel Eaqub says embracing diversity isn’t a ‘want to’ anymore it’s a ‘have to’. Speaking at my CulturePRO masterclass in 2017, he also pointed out the worrying imbalances in education, home ownership and employment.

Fast forward to a few weeks ago when I tuned in to the 2024 NZ Economics Forum at the University of Waikato. I was curious to hear the latest figures on the future demographics of Aotearoa with Professor Paul Spoonley (Massey University), Shefali Pawar (University of Waikato) and Sarah Baddeley (Martin Jenkins).

New Zealand’s demographic shifts over the next 20 years will be characterised by declining fertility rates and an aging population. The nation's fertility rate, currently at 1.58 births per woman, is significantly below the replacement level of 2.1. This decline suggests a future with fewer children, impacting everything from educational needs to labour markets.

New Zealand is also experiencing what Professor Spoonley describes as "hyper-aging," with a growing proportion of older adults compared to young ones, a trend that necessitates a re-evaluation of service delivery and infrastructure planning.

I think about these trends in the context of Taumarunui where I live. It’s not unusual for Māori families to have 6 or more children and 14 or more grandchildren.

The unique demographic transitions of Māori and Pacific populations will contrast sharply with those of Pākehā. With a median age of 26 years for Māori and similarly youthful profiles for Pacific communities, these groups represent a significant portion of New Zealand's future workforce. Shefali Pawar says the "demographic dividend" offered by these younger populations could be a boon for the country's economic development, provided there are equitable access and opportunities for education and employment.

By 2043, nearly one-third of New Zealand's child population will be Māori and Pacific, highlighting the necessity for tailored educational and developmental programmes.

Aaron Smale wrote about New Zealand’s yawning demographic divide last year with demographer Tahu Kukutai.

But it bears repeating that the aging non-Māori population and the potential for increased dependency ratios raises questions about the sustainability of current economic and social structures. Sarah Baddeley says sectors like healthcare and housing need to be adaptable to accommodate an older demographic while still providing for the youthful dynamism of Māori and Pacific populations.

As the population ages and the workforce shrinks, New Zealand will need to rely on immigration to fill the gap. This is already happening, and Auckland is now the fourth most diverse city in the world.

The future of Aotearoa, shaped by these demographic trends, requires a multifaceted approach to policy-making. Initiatives must consider the diverse needs of an aging population alongside the aspirations and potential of younger Māori and Pacific cohorts. Educational systems, workforce development, and infrastructure planning must all be recalibrated to address the realities of a changing demographic landscape.

For Māori and Pacific peoples, the future holds promise if strategies are put in place now to ensure equitable access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Policies must be culturally sensitive and inclusive, recognising the unique contributions and needs of these communities.

The Culture and Design Lab empowers workplace leaders to create social cohesion at work. We use indigenous knowledge, design, and strategy to foster inclusion and belonging in the workplace.